Chalkbrood disease is caused by the fungus Ascosphaera apis. The fungus rarely kills infected colonies but can weaken it and lead to reduced honey yields and susceptibility to other bee pests and diseases.

Young infected larvae do not usually show signs of disease but will die upon being sealed in their cells as pupae. Worker bees will uncap the cells of dead larvae, making mummies clearly visible, before sometimes removing the mummified larvae and depositing them on the hive floor or at the entrance to the hive.

Chalkbrood disease is present throughout most of Australia and its incidence is generally higher when a colony is subject to temperature changes, particularly cooler weather, or other sources of stress.

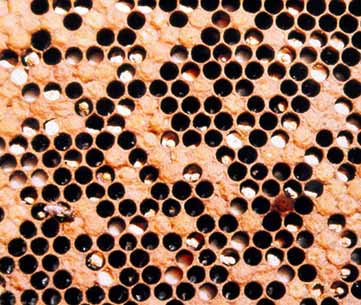

Comb infected with Chalkbrood disease showing a scattered brood pattern with mummies in cells. Food and Environment Research Agency (Fera), Crown Copyright

Chalkbrood disease is not usually a serious disease, as healthy honey bee colonies will usually be able to tolerate it. The incidences are generally higher when a colony is subject to temperature changes or other sources of stress. Some stressors on the colony may include long periods of wet or dry conditions, poor nutrition, a failing queen bee or the movement of hives.

Chalkbrood disease is most common in the spring when temperatures are cooler but the brood is rapidly expanding and the smaller honey bee workforce cannot maintain brood nest temperature. Usually the first larvae that are affected by Chalkbrood disease are those developing around the edges of the brood where brood nest temperatures are harder to maintain. The stages of Chalkbrood disease are as follows:

Chalkbrood starting to envelop a developing pupa. Rob Snyder, www.beeinformed.org

Infection occurs when the larvae ingest the fungal spores with their food. Unlike other pathogenic fungi which can infect the bee larvae externally, A. apis can only infect if it is ingested. Once ingested the spore produces long filaments (known as hyphae) which penetrate the larva’s gut wall in order to absorb nutrients from the larva. Ultimately the germinating spore causes the larva to die of starvation. Larvae infected with Chalkbrood disease usually die after capping.

Nutrients are absorbed through parts of fungi known as mycelium, which appear as the visible fluffy, white fungal growth – similar to white mould on bread or very fine cotton wool. After a few days of growing within the larva’s body the mycelium breaks out of the end of the larva, typically leaving the head unaffected. The larva and fungus swells until it fills the cell it is contained in, then after a few days the white fungal growth hardens, adopting the cell’s hexagon shape, to form a white, chalk-like ‘mummy’ which gives the disease its name.

Larvae being replaced by Chalkbrood fungal mycelium. Rob Snyder, www.beeinformed.org

The mummified larva will transition from a white to grey-black colour, which shows the completion of the fungal life cycle and the creation of new spores capable of infecting a new larval host. These spores will remain capable of infecting other bee larvae for up to 15 years. Each Chalkbrood mummy will produce millions of spores which stick to hive components, pollen and adult bees. Spread typically occurs when there is an accumulation of mummies beyond the worker bees’ capacity to manage. If worker bees remove mummified larvae from the hive before the spores are produced (before the mummified larvae transitioning to the grey-black colour), the spread of the fungus within the hive will be limited.

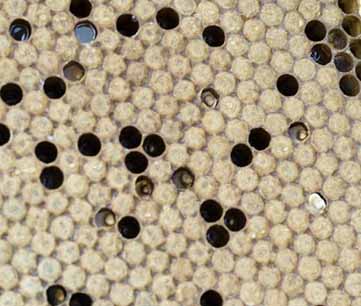

Chalkbrood infected brood. Note the infected brood cells with no capping. Doug Somerville, NSW DPI

Symptoms of Chalkbrood may only appear for a short time, typically in cold and damp weather conditions. However, viable fungal spores can be present in and around the hive for 15 years. When symptoms of Chalkbrood disease do appear, diagnosing an infected hive with the disease can be done easily using visual detection methods. A beekeeper will be able to diagnose an infected hive based on the presence of the hard, shrunken chalk-like mummies in the brood and in and around the entrance to the hive. The mummies will be white to grey-black in colour.

Infected hives also show a scattered brood pattern or appearance. The cell caps of dead larvae may contain small holes, appear slightly flattened or have been chewed away by the honey bees. Worker bees will usually uncap the cells of dead larvae, making mummies clearly visible, before sometimes removing the mummified larvae and depositing them on the hive floor or at the entrance to the hive. In heavily infected colonies the worker bees will not be able to uncap all of the affected cells. Mummies still in uncapped cells may fall from the comb when it is inspected. If mummies are still contained in capped cells, when a comb is shaken gently the mummies may be heard rattling in the cells. During inspection, a beekeeper should gently shake bees from the frame to allow a full and free view of the brood.

Chalkbrood infested brood. Rob Snyder, www.beeinformed.org |

Chalkbrood disease symptoms of scattered brood pattern with perforated cell caps could be confused with either American foulbrood (AFB), European foulbrood (EFB) or Sacbrood virus. However, the presence of mummies in the cells, the hive entrance and bottom boards, together with no ropey thread when conducting the ropiness test, would suggest the presence of Chalkbrood disease. Some distinct symptoms and indicators of these similar pests include:

|

American foulbrood with perforated cappings. Rob Snyder, www.beeinformed.org |

American foulbrood

|

European foulbrood in the latter stages, showing lots of scale in the bottom of the brood cells. Rob Snyder, www.beeinformed.org |

European foulbrood

|

Infected larvae change to dark brown-black as the disease progresses. Rob Snyder, www.beeinformed.org |

Sacbrood virus

|

Chalkbrood ‘mummies’ being deposited at the hive entrance. Rob Snyder, www.beeinformed.org

The fungal spores that cause Chalkbrood disease are highly infectious and can be easily spread between hives through the drifting behaviour of drones and worker bees, as well as the robbing behaviour of worker bees. Once inside a hive, fungal spores are quickly spread throughout the hive from mummies and the activity of worker bees. Spread of the fungus mostly occurs through the activities of beekeepers as the spores can be transferred between apiaries on contaminated equipment, pollen and in water. Shifting bees on trucks with an open entrance can cause drift which also spreads the fungal spores. Infected foraging bees may also leave spores at floral and water sites. The Chalkbrood spores may remain viable for up to 15 years or even more in equipment and soil.

Mummies on the hive floor. Food and Environment Research Agency (Fera), Crown Copyright

Chalkbrood disease is present throughout Australia. The incidence of Chalkbrood disease is generally higher when the colony is under stress due to cool wet weather or poor nutrition. It is more common in the spring when the brood nest is rapidly expanding and a smaller honey bee workforce cannot maintain brood nest temperature.

As well as being present in Australia, Chalkbrood disease also has a broad distribution internationally and is present on all continents.

Beekeepers and apiary inspectors should be aware of the reporting requirements for all states and territories in Australia. Certain states and territories require reporting to government authorities within a certain time period, so check with the state or territory’s relevant agricultural department.

There are no registered chemicals available to control Chalkbrood disease, and chemical treatments should be avoided due to their ability to contaminate honey products and honey bees. Healthy bee colonies will be able to tolerate Chalkbrood disease. Beekeepers should remember the simple points outlined below to help avoid any outbreak of Chalkbrood disease in honey bee colonies.

Beekeepers should replace diseased comb with new combs (with new foundation) because the diseased comb can act as a reservoir for Chalkbrood disease spores. It is also necessary to clean away mummified larvae from the bottom boards and around the entrance of the hive. These activities will remove the main source of infection within a hive, and prevent the spread of the disease amongst other hives.

Hives should be placed in a well-ventilated, dry area where the sun is facing the entrance of the hive to reduce conditions that favour the disease (cold, damp and poorly ventilated environments). Changes in brood-nest temperature can trigger Chalkbrood disease outbreaks and typically the first larvae to be affected are those around the edges of the brood where temperatures fluctuate. Therefore, beekeepers should avoid practices that can lead to loss of heat from the hive such as removing adult bees from a hive, give a hive extra brood to rear, or add on extra supers at the wrong time. Beekeepers should also reduce the volume of the brood chamber during the winter period to preserve brood temperatures and to allow the bees to maintain a strong winter cluster.

The maintenance of the health of the hive may also require supplementing the bee’s diet with sugar syrup and fresh uncontaminated pollen when nutrition is poor.

A key aspect of good colony management also involves the beekeeper reducing or preventing the interchange of hive materials that can spread the fungal spores. If you notice that some hives are infected with Chalkbrood disease, clean your beekeeping gear before inspecting a new apiary.

The main way that pests and diseases are spread between hives and apiaries is through the transfer of infected materials and disease contaminated equipment. Unfortunately, it is not always possible to know if equipment is contaminated, so it is better to be cautious to prevent spreading the pest or disease from infected to healthy colonies. One way to reduce any possible transfer is to use a barrier management system.

The barrier management system is used to separate hives or apiaries into different units. This prevents the interchange of honey bees, combs, honey and hive components from one unit (hive, loads of hives or apiary) to another. The adoption of this system can also enhance traceability, biosecurity and quality assurance aspects of the beekeeping enterprise, as well as building on best practice principles.

Chalkbrood ‘mummies’ being deposited at the hive entrance. Rob Snyder, www.beeinformed.org

The variation in susceptibility between different honey bee stocks is due to differences in the hygienic ability of honey bees to detect, uncap and remove diseased brood. Bees with good hygiene habits will usually remove mummies before the formation of the infectious spore. Beekeepers may need to replace an infected colony’s queen bee with one supplied by a reputable breeder or a queen bee selected from a hive that shows good hygiene traits in order to reduce the effects of Chalkbrood disease.

Additional fact sheets from Australia and from around the world, which provide extensive information about this pest, have been listed below. To learn more, click on the links below:

Chalkbrood disease, Plant Health Australia

Chalkbrood recommendations, University of Florida

Chalkbrood, Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries

Australian Beekeeping Guide (2014) Agrifutures Publication No. 14/098